.png?command_1=resize&width_1=220)

Support or Shortcut?

📞 Need Tech Help? Tech questions? We're here to help! Email [email protected] and our team will get back to you as soon as possible during the school day.

Last week, we explored why your child's relationship with AI must be different from yours: they're still building the fundamental cognitive capacities—critical thinking, problem-solving, analytical reasoning—that you've already developed. When AI does that cognitive work for them, it removes the developmental opportunity the assignment was designed to provide.

But here's the practical challenge: How do we actually distinguish between AI use that enhances cognitive development and AI use that shortcuts it? As we've worked to develop Brookwood's approach to AI, we've focused on creating clarity in two directions: foundational expectations, and how to think about the range of appropriate uses.

Clear Boundaries ⚠️

Some uses of AI are simply off the table: using AI to complete work you're claiming as your own, bypassing the cognitive work an assignment was designed to develop, using unauthorized AI platforms, or sharing personal information with AI systems. These aren't arbitrary rules—they flow directly from our commitment to your child's cognitive development and creating a safe learning environment.

A Framework for Thinking 🧠

But "don't cheat" and "don't bypass learning" aren't enough guidance when a student is wondering whether they can use AI to brainstorm ideas, check grammar, or debug code. Not all AI use is the same.

Here's an additional complexity: AI is increasingly embedded in tools we use without a second thought. Grammarly uses AI underneath. Google Docs has AI-powered features. Even spell-check has become more sophisticated with machine learning. The line between "regular software" and "AI" is blurring, making simple blanket rules nearly impossible.

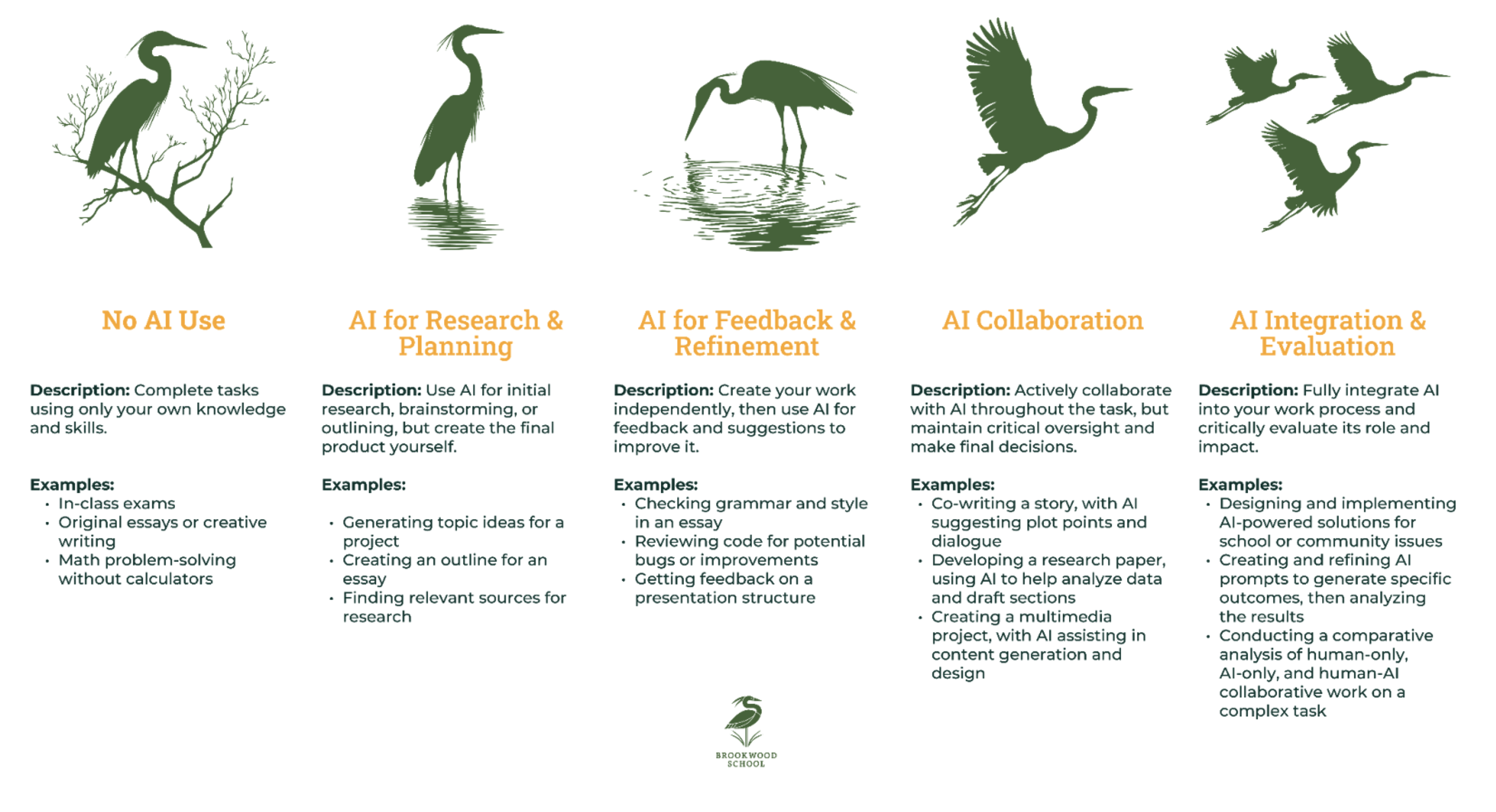

We've developed what we call an AI Use Spectrum—a framework that helps teachers and students think about five different levels of AI integration, ranging from no AI use at all to full AI collaboration with critical evaluation. Some teachers are using this spectrum to label assignments clearly; others are using it as a thinking tool; still others are developing their own ways of communicating expectations that align with these principles. The point is creating a shared vocabulary and common understanding of how AI fits into the learning process.

What This Looks Like 👀

A math teacher might say: "You can use AI to check your work after you've solved the problems, but not to solve them for you."

An English teacher might create a custom AI tutor that asks guiding questions—"What evidence supports that claim?"—rather than giving outlines or writing paragraphs.

A history teacher might allow AI for initial research but require that final analysis come entirely from the student's own thinking.

The Opportunities 🔑

When used thoughtfully, AI opens up learning experiences that weren't possible before. It can serve as a tireless thinking partner, provide immediate personalized feedback, and offer scaffolding for students who struggle with certain aspects of learning. The technology creates opportunities for personalization at scale, meeting students where they are and adapting to their needs. The key: the student is still doing the cognitive work—thinking, analyzing, synthesizing, creating. AI enhances their capacity to do that work, not replacing it.

This is why we're approaching AI with thoughtful boundaries and genuine excitement about what becomes possible when we get it right, while protecting the essential developmental work that schools exist to support.

We're Still Learning 🍎

We're one school year into this experiment. Teachers are calibrating their approaches in real time, and what we do have is a commitment to being proactive, learning alongside our students, and maintaining focus on that central question: Is this use of AI supporting cognitive development or bypassing it?

What This Means at Home 🏡

When your child asks about using AI for homework, the first step is to check what their teacher has communicated. If expectations aren't clear, your child should reach out to their teacher. And if you're uncertain? Email the teacher. The underlying principle remains the same: we're looking for the cognitive work to happen in your child's mind, not in the AI. When in doubt, err on the side of having your child do more of the thinking themselves.

What I'm Reading: Non-things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld by Byung-Chul Han. I've just started this one, and Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han has an interesting take on our digital moment. His basic argument is that we're replacing the world of physical things with what he calls the "infosphere"—this constantly expanding realm of information and communication. Think Google Earth instead of actual earth, the Cloud instead of the sky. What strikes me so far is his observation that we search endlessly for information without gaining real knowledge, communicate constantly without participating in real community, and accumulate friends and followers without actually encountering people. Everything becomes "non-things"—information without the weight and stability of material objects. It feels like a companion piece to The Right to Oblivion, but approaching the same concerns from a different angle: not just about what happens when everything becomes data, but about what we lose when the physical world itself starts to fade from view.

.png)